Almost every day, I hear someone talking about their core, usually stating that they need to strengthen it or that having a stronger one [core] will cure their back pain… mmm [sigh].

Here’s a recent example; a new patient, let’s call him mister B, shared with me that his trainer had told them they needed to “build-up their core to fix their long-term back problem”. “Do more planking and up your reps (repetitions) of boxers crunches.” (a lying down head to knee spinal flexion movement), but it wasn’t working.

His back pain had become significantly worse since taking this advice; he pointed to his “super tight six-pack” (abdominals) as he recalled his story and was a tad bewildered why he was sitting in my treatment room; in pain!. I’m sure his trainer had good intentions. Still, I worry when I hear these misguided, outdated statements about any aspect of health or wellbeing, but [sigh] the core thing raises my hackles …. argh!

What is the core, and is it important?

No fessing up needed; you guessed I’m not too fond of the term ‘core’; it makes me think of the innards of an apple. Yep, I probably need to get over it and myself, but will use it for ease of language for the time being.

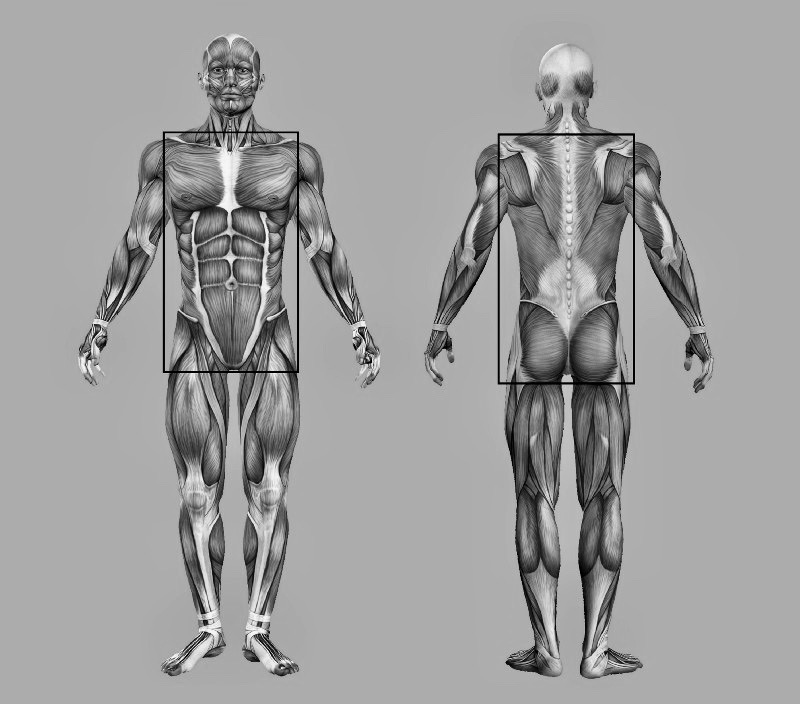

Scientifically the ‘core’ is called the lumbopelvic-hip complex (LPHC). However, it’s the whole of your torso or trunk. Everything attached to your head, arms, and legs, including the lower back, pelvis, and hips, should also include shoulders and buttocks.

A helpful way to understand the LPHC is to think about it as a group of muscles connected to the spine and pelvis. Humans hide many of these muscles deep beneath the skin and exterior musculature that people typically train, i.e. the “super tight six-pack” mister B mentioned. In his case, his abdominals were rigid and limiting any ability to be functionally mobile and part of the aggravating factor in his ongoing pain. Think of a classic rigid daddy dancing man; that’s mister B.

The deeper hidden muscles include the transverse abdominis, multifidus, diaphragm, pelvic floor, and many others. When working well, these muscles efficiently speed up, decelerate and dynamically control (stabilise) human movement in all planes and directions.

The LPHC (lumbopelvic-hip complex) is a bit of a clinical mouthful, so the term ‘core’ has become mainstream and synonymous with stability. Also known as core stabilisation, but there are many definitions of core stabilisation or stability; here are 3:

- A term used to describe the ability to maintain spinal and pelvic alignment using trunk and hip muscle endurance and strength.

- Core stabilisation is the action where muscles stabilise the spine statically or dynamically while other muscles carry out movement involving other joints.

- Core stabilisation is the ability to control the position of the torso and its motion over the pelvis. To optimise force control and motion in distal segments as needed.

In plain English, stiffening the spine with a group of muscles so that humans can move and control their position in space. So, you don’t fall over when reaching up with one arm to get your favourite coffee mug off a high shelf.

Superficial torso muscles in outlined boxes.

Why the fuss?

Optimal “core” function involves both mobility and stability of the torso; when it [the “core”] functions well, people can produce effective movement with their arms and legs and maintain their centre of gravity over their feet. Although, the ribcage doesn’t have to stay over the pelvis or feet to remain stable. Nor does it have to go everywhere your pelvis does unless you want to move like a robot.

In an ideal world, humans should be able to place and move their pelvis and ribcage independently like a Cuban salsa dancer – and there’s some isolated body movement of some beauty! Oh, and most of those dancers have fantastic core stability because it’s dynamic and functional, but some have back low pain too!

The core stability myth.

Myths and misconceptions are very hard to dispel once they have become established as norms. Despite being exposed nearly ten years ago, the core stability myth remains. Some people, including health professionals and fitness experts, continue to hold the belief that having a stronger core will reduce or fix back pain. Give people better posture and help them shine in sporting activities. The only people I have met with torso muscles so weak that they couldn’t achieve “good posture” were those with neurological conditions or acute injuries.

A little history.

The term core stability appeared in fitness language late in 1996 from the published studies of Prof. Paul Hodge, from Queensland University Australia. His studies on a deep abdominal muscle called the transversus abdominis (TrA). Using two groups of people, one group with no history of back pain and another with chronic back pain, it lasted over 12 weeks. His results showed that the healthy group engaged their TrA just before moving, which offered their spine support. However, in the chronic back pain group, TrA engagement did not occur, resulting in their spine being less supported.

From these findings, Hodges claimed that the TrA muscle could be strengthened by “drawing in” the abdomen (stomach/belly) during exercises, and this would provide some protection against back pain. Hodges’s findings coupled with beliefs and assumptions around at the time about the importance of the abdominal muscles to maintain a healthy, pain-free back.

It’s worth noting that this was not a new concept; Professor Freeman, a British orthopaedic surgeon, had discussed this in 1965 when exploring the motor strategies and foot instability that take place after an ankle injury.

Later research by Hodges and others exposed that perhaps the real issue wasn’t one of strength but poor coordination and delay in the timing of muscles in people with chronic back pain. Despite this clarification, the concept of core stability and strengthening spread like a bush fire ( ell he is an Aussie). Hodges is a physiotherapist, so it’s easy to see how this spawned a massive market in core work as a prerequisite in the fight against back pain and postural problems (that’s another story) with his fellow manual therapists.

Despite Hodges trying to clarify and correct this misconception, core exercise classes based on his original work popped up everywhere worldwide. In the late ’90s, core stability and Pilates classes achieved cult status worldwide with everyone engaging their TrA; at the traffic lights, while waiting for the kettle to a boil, walking around and sometimes all the time!!! Pilates became the core class of choice for many because it was just breaking into the mainstream around the same time, a recipe of perfect timing… pun intended.

In 2007 Prof Eyal Lederman, a fellow osteopath with a PhD in physiotherapy, took an in-depth look into this subject. His paper, “the myth of core stability”, upset and confused many; physiotherapists, personal trainers, classically trained Pilates instructors, and others offering core training. It made me wobble, too; I’m a classically trained Pilates teacher. Was I causing harm? Wasting folks time? I read his paper several times, listened to his talks and spoke to him in person.

While I might be a Pilates teacher, I don’t teach core training. I teach movement; I rarely, if ever, ask people to contract their abdominal muscles before moving; it’s counter-intuitive to motor learning principles. I tell my patients/clients this all the time: you don’t reach up to get your favourite coffee cup out of a cupboard by focusing on your muscles. You move your arm and muscle switch on as needed to achieve your desired task. Whether in group classes or individual rehabilitation sessions, my focus in sessions has always been on performance improvement rather than muscle activation.

Can you have too much core stability?

A study in 2003 showed that when core muscles contract, they exert a compressive force on the lumbar spine. Well, that’s the point – to create spinal stiffness. Yet, this is likely to increase compression on already sensitised spinal joints, and for people with chronic low back pain, especially those with disc problems, potentially it makes their back pain worse. These are usually the folks seeking out a pilates class or core training in their desperate quest for a solution, but many slide in a vicious cycle.

Summary – too much static core stability increases intra-abdominal pressure, spinal compression and often results in more discomfort; remember, mister B?

An increase in intra-abdominal pressure could be a further complication of contracting the trunk muscles. Studies from 2006 suggest that patients with pelvic girdle pain who exercise with this focus could exert potentially damaging forces on various pelvic structures, including ligaments and the pelvic floor muscles — for example, bracing to hold a plank exercise for long periods. These groups should be encouraged and supported to reduce their intra-abdominal pressure, with relaxation techniques and breathing exercises, should avoid core work and instead aim to restore normal reactive contraction, not bracing; think turning up and down a dimmer switch rather than flicking on and off.

Did you know – that core muscles, especially the pelvic floor, naturally contract in response to hand and arm movements? Probably to stop you voiding your bladder (wetting your pants) when you sneeze, that’s pretty useful, but there is no need to hold a contraction all the time just in case.

Is planking your way to a stronger core?

Still not convinced? Here is more research; Professor Stuart McGill, a biomechanics expert from the University of Waterloo in Canada, showed that the amount of load the spine could bear was significantly reduced when subjects braced their abdominals by “sucking in their belly buttons”. He reputes that when the muscles are “pulled” closer to the spine, it reduces stability. “People become weak and wobbly as they try to move”, the opposite of what they are trying to achieve.

Another (perhaps better) way forward

Core training alone offers a very simplistic solution to an often complex and multifactorial problem. People affected by pain often remain poorly educated about the real causes or maintaining factors of their condition or how to effectively manage it, leading to a pattern of chronicity or down a road of despair.

When it comes to back pain, whether persistent or recurrent, research has shown that psychological and psychosocial factors are more critical factord to address because much of the pain we experience results from how we react to our internal and external environment.

The human spine needs to move and explore all its range of potential movement, especially if you spend the bulk of your day static or sitting. While I love Pilates and want folk to reap its benefits too, it’s not for everyone. Fortunately, research shows time and time again that any exercise or movement practice beyond your everyday activities can help a back problem and build overall strength.

Final words

Without or without back problems, folks can develop a dynamic torso (core) and resilient anti-fatigue body by moving more of themselves, more frequently. Find something you enjoy and are willing to do regularly for 30–60 minutes, 2–5 times a week. It should include pushing, pulling, twisting, flexing, extending, bending, arching, lifting loads, and jumping around if you can.

Take home message; most humans simply need to move more of themselves more often.

Footnote: I mentioned the “CORE” 36 times… yikes!