Pressure and stress are omnipresent; touching every aspect of our everyday life, affecting our body, thoughts, our feelings, and our behaviours too. Interestingly, although most people believe that all stress is harmful, it has some essential benefits.

The sabre-toothed tiger we face today is more likely to be commuting problems, work pressure. Or a family crisis, but our body’s emergency system responds in the same way. There is an optimum level of pressure that brings about our best performance. It allows us to take on new challenges, hit targets, meet deadlines or accept change, but crucially we feel in control.

Science defines stress as the feelings of being under too much mental or emotional pressure, where we don’t have control. Our current use of the term stress originated in the 1940s by the pioneering endocrinologist Dr Hans Selye he coined the following terms:

Eustress = good stress.

Selye described this as the stress in daily life that has positive undertones such as a job promotion, planning a wedding or the birth of a baby.

Distress = negative stress

Selye described this as the stress that has a detrimental or negative connotation. For example, relationship breakdowns and divorce. Long-term injury, family illness, work difficulties or financial problems

In the twenty-first century, we hear the word stress banded around, without clarifying if it’s beneficial or disadvantageous. The stress response is the term used to describe the way the mind and body react to stress.

The Stress Response, here’s the science bit.

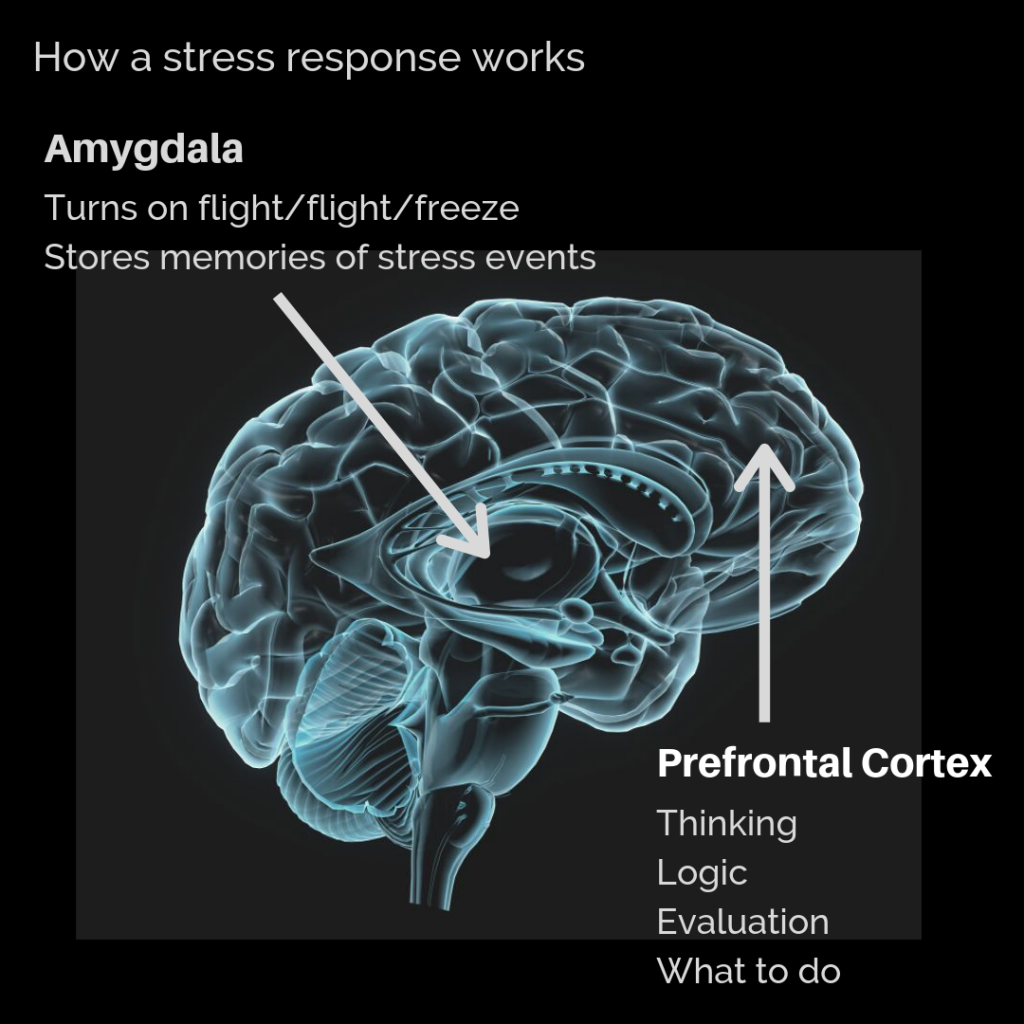

When the brain perceives a threat, remember this can be a real or imagined threat. Our mind and body respond by triggering the rapid release of hormones and chemicals into the bloodstream. These aim to bring about specific physical, mental and emotional reactions, to intensify the body’s ability to deal with the threat with a fight-flight-freeze response.

Adrenaline is the short-term response the body releases from the adrenal glands which sit on top of the kidneys. Adrenaline makes us breathe faster; increases heart rate and elevates blood pressure boosting energy. These reactions create tense muscles and increase strength, just in case we need to run away. Another effect of Adrenaline is that it suppresses the immune system; fighting off illness is not a priority when you are running away from a predator.

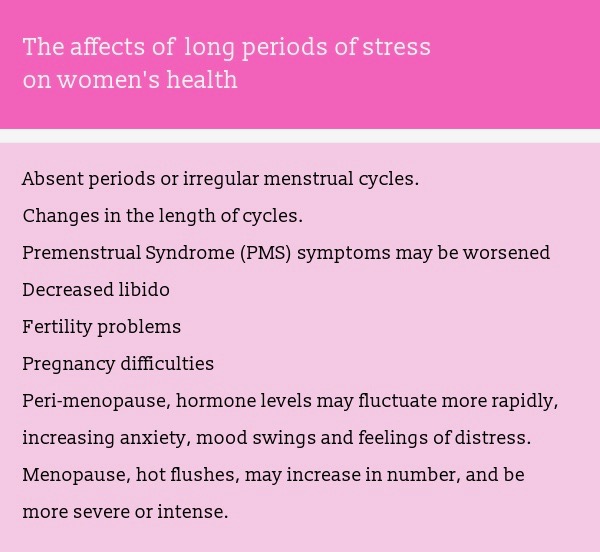

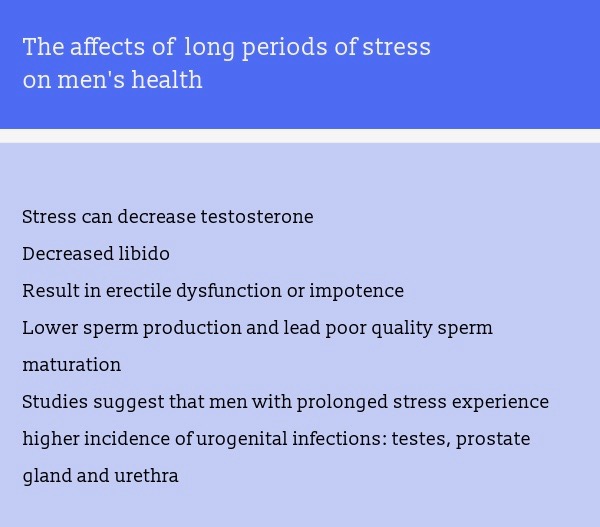

Cortisol increases the level of sugar in the bloodstream to help the brain use glucose, which causes an increase in the substances that repair tissues and stop us feeling pain. Just in case we need to run away from a predator with a sprained ankle, or a broken arm. Another effect of Cortisol is that it halts nonessential body functions or those detrimental in a fight-flight-freeze situation. It suppresses the digestive system, the reproductive system, and growth. Digesting food or growing a baby is not a priority if you are under attack.

Adrenaline, just like Cortisol also depresses the immune response, but it increases inflammation and lowers our ability to fight infections and resists disease. Which explains why some people get repeated coughs and colds or always seem unwell when they report feeling stressed. Or as Selye would say are distressed. Repeated viral infections can also be a sign that someone is stressed, which they may not realise. These hormonal and chemical changes, what some people refer to as a chemical soup happen so quickly that we often aren’t aware of them at all.

Here’s a little more science:

What’s remarkable is that the brain-body wiring is so efficient that we often experience a split-second reaction. Our primitive brain; the Amygdala and Hypothalamus start a cascade of events before the brain’s visual centres have processed what is happening. Brilliant if you need to grab a child reaching for something hot. Or dart out of the way of a speeding danger.

The stress-response is usually self-limiting, so once the perceived or real threat has passed, Adrenaline, Cortisol and other hormone levels return to normal. The heart rate and blood pressure drop to baseline levels and other body systems resume their normal activities. It takes about 90 minutes for the metabolism to return to normal after the stressful event is over. Short periods of stress are not harmful; in fact, they are necessary to ensure our survival.

It’s a complex natural alarm system, but our reaction to stressful events is individual, which makes this complicated. Many factors, including genetics and previous experiences, communicate with the brain to control mood, motivation, and fear and can influence our stress response. You will know people who seem super relaxed about almost everything and others who react strongly to the slightest adversity. Symptoms associated with stress can include:

- Aches and pains especially in the back, neck, and shoulders.

- Jaw pain, usually from unconscious clenching or bruxism (grinding) of teeth.

- Headaches and migraine.

- Stomach ache and digestive problems such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Inability to relax, fidgety and unsettled.

- Poor sleep or insomnia.

- Weight gain especially around the waist.

- Feeling low or depressed.

Why the fuss?

If the stressor doesn’t go away or returns quickly, our natural stress response system goes haywire. Prolonged stress can be detrimental because it affects every aspect of our health and wellbeing, and can lead to an array of problems. The most obvious is behavioural changes, such as a lack of focus, decrease work performance, poor concentration, and attention, or failing memory. It can cause reduced self-confidence, low mood, anxiety, and social withdrawal, becoming a vicious, misunderstood cycle.

External vs internal stressors

How do you react to unpredictable events such as:-

- Uninvited houseguests.

- Demanding clients?

- Endless emails?

- Urgent deadlines

- An overly critical line manager?

- Meeting new people or if you are single going on a blind date?

While most people understand that input from the world can be a source of stress, sometimes our reaction is not appropriate or proportionate. Consider how you react to sudden noises, such as an emergency vehicle whizzing past you, or a dog barking? How you take the news of your neighbours having an unplanned party? Or feel walking into a bright sunlit room?

Why do I ask these questions? Because not all stress stems from things that happen to us; much of our stress is self-induced. Our feelings, beliefs, and thoughts influence how we react to stress. We may not think about how this has shaped our experience, but these preset thoughts can nudge us into a persistent stress stage. Common ones include fear of failure, public speaking, and uncertainty. It is so easy for these to become self-sabotaging behaviours. Consider the expectations you put on yourself to create a perfect children’s or dinner party, wearing an on-point outfit for a night out. Or how you advance up the career ladder.

What helps

Our body strives to reach a state of internal balance, called homeostasis, while our mind is seeking contentment or happiness. It seems straightforward in principle but can be a challenge in practice. Sorry, that’s an understatement, if you are reading this and struggling with symptoms of stress, it can seem impossible. However, there are solutions. I believe that with an understanding of how and why stress happens, you can regain control. Remember the difference between pressure and distress is whether we feel in control. Information and knowledge can help you make positive changes, but before that, let me confirm a few truths. If you are currently struggling with high stress; you are neither weak, lack willpower or merely lazy.

Effective stress management requires a multidisciplinary approach, which should, in my opinion, start with education. And my patients tell me that information helps, so I hope this article is useful to you too.

There is no universal stress reduction strategy, I hear you groan, but this is excellent news because it means there are options and choice. Regardless of the science, research, and evidence, the best stress management and treatment for you is the one that works – for you.

With knowledge, you have choices, and options can help you create meaningful strategies to manage your stress response. Simple adjustments can help us achieve physical, mental and emotional homeostasis, which has the bonus of helping to increase resilience to future stressors.

Summary

We shouldn’t dread stress because it’s not all bad; feelings of anxiety or fear bookmark some of the most joyful events of life. Fortunately, there is a variety of simple self-help approaches that can help avoid the detrimental health consequences of long-term stress.

Coming in Stress, how it affects your body – part 2 Lifestyle tips to help you manage stress